1755 Lisbon earthquake

| | |

| Date | 1 November 1755 |

|---|---|

| Magnitude | 8.5–9.0 Mw (est.) |

| Epicenter | About 200 km (120 mi) west-southwest of Cape St. Vincent. |

| Countries or regions | Kingdom of Portugal, Kingdom of Spain, Morocco. The tsunami affected Southern Great Britain and Ireland |

| Casualties | 10,000–100,000 deaths |

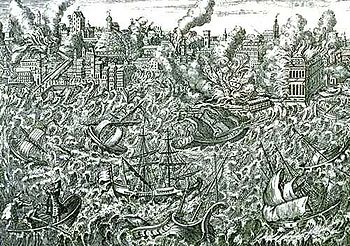

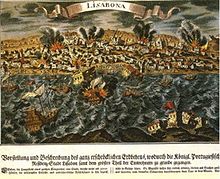

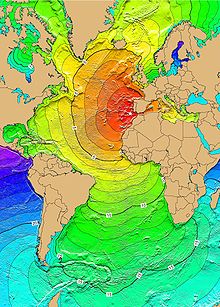

The 1755 Lisbon earthquake, also known as the Great Lisbon Earthquake, occurred in the Kingdom of Portugal on Saturday, 1 November 1755, the holiday of All Saints' Day, at around 09:40 local time.[1] In combination with subsequent fires and a tsunami, the earthquake almost totally destroyed Lisbon and adjoining areas. Seismologists today estimate the Lisbon earthquake had a magnitude in the range 8.5–9.0[2][3]) on the moment magnitude scale, with its epicentre in the Atlantic Ocean about 200 km (120 mi) west-southwest of Cape St. Vincent. Estimates place the death toll in Lisbon alone between 10,000 and 100,000 people,[4] making it one of the deadliest earthquakes in history.

The earthquake accentuated political tensions in the Kingdom of Portugal and profoundly disrupted the country's colonial ambitions. The event was widely discussed and dwelt upon by European Enlightenment philosophers, and inspired major developments in theodicy and in the philosophy of the sublime. As the first earthquake studied scientifically for its effects over a large area, it led to the birth of modern seismology and earthquake engineering.

Earthquake and tsunami

The Azores-Gibraltar Transform Fault, which marks the boundary between the African (Nubian) and the Eurasian continental plates, runs westward from Gibraltar into the Atlantic. It shows a complex and active tectonic behavior, and is responsible for several important earthquakes that hit Lisbon before November 1755: eight in the 14th century, five in the 16th century (including the 1531 earthquake that destroyed 1,500 houses, and the 1597 earthquake when three streets vanished), and three in the 17th century. During the 18th century, earthquakes were reported in 1724 and 1750.

In 1755, the earthquake struck on the morning of 1 November, the holiday of All Saints' Day. Contemporary reports state that the earthquake lasted between three and a half and six minutes, causing fissures 5 metres (15 feet) wide to open in the city centre. Survivors rushed to the open space of the docks for safety and watched as the water receded, revealing a sea floor littered with lost cargo and shipwrecks. Approximately 40 minutes after the earthquake, a tsunami engulfed the harbour and downtown area, rushing up the Tagus river,[5] "so fast that several people riding on horseback ... were forced to gallop as fast as possible to the upper grounds for fear of being carried away." It was followed by two more waves. In the areas unaffected by the tsunami[citation needed], fire quickly broke out, and flames raged for five days.

Lisbon was not the only Portuguese city affected by the catastrophe. Throughout the south of the country, in particular the Algarve, destruction was rampant. The tsunami destroyed some coastal fortresses in the Algarve and, in the lower levels, it razed several houses. Almost all the coastal towns and villages of the Algarve were heavily damaged, except Faro, which was protected by the sandy banks of Ria Formosa. In Lagos, the waves reached the top of the city walls. Other towns of different Portuguese regions, like Peniche, Cascais, and even Covilhã which is located near the Serra da Estrela mountain range in central inland Portugal, were affected. The shock waves of the earthquake destroyed part of Covilhã's castle walls and its large towers. On the island of Madeira, Funchal and many smaller settlements suffered significant damage. Almost all of the ports in the Azores archipelago suffered most of their destruction from the tsunami, with the sea penetrating about 150 m inland.

Shocks from the earthquake were felt throughout Europe[6] as far as Finland and North Africa, and according to some sources even in Greenland[7] and in the Caribbean.[8] Tsunamis as tall as 20 metres (66 ft) swept the coast of North Africa, and struck Martinique and Barbados across the Atlantic. A three-metre (ten-foot) tsunami hit Cornwall on the southern English coast. Galway, on the west coast of Ireland, was also hit, resulting in partial destruction of the "Spanish Arch" section of the city wall. At Kinsale, several vessels were whirled round in the harbor, and water poured into the marketplace.[8]

Although seismologists and geologists had always agreed that the epicentre was in the Atlantic to the West of the Iberian Peninsula, its exact location has been a subject of considerable debate. Early theories had proposed the Gorringe Ridge until simulations showed that a source closer to the shore of Portugal was required to comply with the observed effects of the tsunami. A seismic reflection survey of the ocean floor along the Azores-Gibraltar fault has revealed a 50 km-long thrust structure southwest of Cape St. Vincent, with a dip-slip throw of more than 1 km, that might have been created by the primary tectonic event.[9]

Casualties and damage

Economic historian Álvaro Pereira estimated that of Lisbon's population of approximately 200,000 people, some 30,000–40,000 were killed. Another 10,000 may have lost their lives in Morocco; however, a 2009 study of contemporary reports relating to the 1 November event found them vague, and difficult to separate from reports of another local series of earthquakes on 18–19 November.[10] Pereira estimated the total death toll in Portugal, Spain and Morocco from the earthquake and the resulting fires and tsunami at 40,000 to 50,000 people.[11][12]

Eighty-five percent of Lisbon's buildings were destroyed, including famous palaces and libraries, as well as most examples of Portugal's distinctive 16th-century Manueline architecture. Several buildings that had suffered little earthquake damage were destroyed by the subsequent fire. The new Opera House, opened just six months before (named the Phoenix Opera), burned to the ground. The Royal Ribeira Palace, which stood just beside the Tagus river in the modern square of Terreiro do Paço, was destroyed by the earthquake and tsunami. Inside, the 70,000-volume royal library as well as hundreds of works of art, including paintings by Titian, Rubens, and Correggio, were lost. The royal archives disappeared together with detailed historical records of explorations by Vasco da Gama and other early navigators. The earthquake also damaged major churches in Lisbon, namely the Lisbon Cathedral, the Basilicas of São Paulo, Santa Catarina, São Vicente de Fora, and the Misericórdia Church. The Royal Hospital of All Saints (the largest public hospital at the time) in the Rossio square was consumed by fire and hundreds of patients burned to death. The tomb of national hero Nuno Álvares Pereira was also lost. Visitors to Lisbon may still walk the ruins of the Carmo Convent, which were preserved to remind Lisboners of the destruction.

Relief and reconstruction efforts

The royal family escaped unharmed from the catastrophe: King Joseph I of Portugal and the court had left the city, after attending mass at sunrise, fulfilling the wish of one of the king's daughters to spend the holiday away from Lisbon. After the catastrophe, Joseph I developed a fear of living within walls, and the court was accommodated in a huge complex of tents and pavilions in the hills of Ajuda, then on the outskirts of Lisbon. The king's claustrophobia never waned, and it was only after Joseph's death that his daughter Maria I of Portugal began building the royal Ajuda Palace, which still stands on the site of the old tented camp. Like the king, the prime minister Sebastião de Melo (the Marquis of Pombal) survived the earthquake. When asked what was to be done, Pombal reportedly replied "Bury the dead and heal the living,"[13] and set about organizing relief and rehabilitation efforts. Firefighters were sent to extinguish the raging flames, and teams of workers and ordinary citizens were ordered to remove the thousands of corpses before disease could spread. Contrary to custom and against the wishes of the Church, many corpses were loaded onto barges and buried at sea beyond the mouth of the Tagus. To prevent disorder in the ruined city, the Portuguese Army was deployed and gallows were constructed at high points around the city to deter looters; more than thirty people were publicly executed.[14] The Army prevented many able-bodied citizens from fleeing, pressing them into relief and reconstruction work.

The king and the prime minister immediately launched efforts to rebuild the city. On 4 December 1755, little more than a month after the earthquake, Manuel da Maia, chief engineer to the realm, presented his plans for the re-building of Lisbon. Maia presented five options from abandoning Lisbon to building a completely new city. The first plan was to rebuild the old city using re-cycled materials; this was the cheapest option. The second and third plans proposed widening certain streets. The fourth option boldly proposed razing the entire Baixa quarter and "laying out new streets without restraint". This last option was chosen by the king and his minister.[15]

In less than a year, the city was cleared of debris. Keen to have a new and perfectly ordered city, the king commissioned the construction of big squares, rectilinear, large avenues and widened streets – the new mottos of Lisbon.

The Pombaline buildings are among the earliest seismically protected constructions in Europe. Small wooden models were built for testing, and earthquakes were simulated by marching troops around them. Lisbon's "new" downtown, known today as the Pombaline Downtown (Baixa Pombalina), is one of the city's famed attractions. Sections of other Portuguese cities, like the Vila Real de Santo António in Algarve, were also rebuilt along Pombaline principles.

The Casa Pia, a Portuguese institution founded by Maria I (known as A Pia, "Maria the Pious"), and organized by Police Intendant Pina Manique in 1780, was founded following the social disarray of the 1755 Lisbon earthquake.

Effect on society and philosophy

The earthquake had wide-ranging effects on the lives of the populace and intelligentsia. The earthquake had struck on an important church holiday and had destroyed almost every important church in the city, causing anxiety and confusion amongst the citizens of a staunch and devout Roman Catholic city and country, which had been a major patron of the Church. Theologians[citation needed] would focus and speculate on the religious cause and message, seeing the earthquake as a manifestation of divine judgement. Most philosophers rejected that on the grounds that the Alfama, Lisbon's red-light district, suffered only minor damage.

The earthquake and its fallout strongly influenced the intelligentsia of the European Age of Enlightenment. The noted writer-philosopher Voltaire used the earthquake in Candide and in his Poème sur le désastre de Lisbonne ("Poem on the Lisbon disaster"). Voltaire's Candide attacks the notion that all is for the best in this, "the best of all possible worlds", a world closely supervised by a benevolent deity. The Lisbon disaster provided a counterexample. As Theodor Adorno wrote, "[t]he earthquake of Lisbon sufficed to cure Voltaire of the theodicy of Leibniz" (Negative Dialectics 361). In the later twentieth century, following Adorno, the 1755 earthquake has sometimes been compared to the Holocaust as a catastrophe that transformed European culture and philosophy. Jean-Jacques Rousseau was also influenced by the devastation following the earthquake, whose severity he believed was due to too many people living within the close quarters of the city. Rousseau used the earthquake as an argument against cities as part of his desire for a more naturalistic way of life.[citation needed]

The concept of the sublime, though it existed before 1755, was developed in philosophy and elevated to greater importance by Immanuel Kant, in part as a result of his attempts to comprehend the enormity of the Lisbon quake and tsunami. Kant published three separate texts on the Lisbon earthquake. The young Kant, fascinated with the earthquake, collected all the information available to him in news pamphlets, and used it to formulate a theory of the causes of earthquakes. Kant's theory, which involved the shifting of huge subterranean caverns filled with hot gases, was (though ultimately shown to be incorrect) one of the first systematic modern attempts to explain earthquakes by positing natural, rather than supernatural, causes. According to Walter Benjamin, Kant's slim early book on the earthquake "probably represents the beginnings of scientific geography in Germany. And certainly the beginnings of seismology."

Werner Hamacher has claimed that the earthquake's consequences extended into the vocabulary of philosophy, making the common metaphor of firm "grounding" for philosophers' arguments shaky and uncertain: "Under the impression exerted by the Lisbon earthquake, which touched the European mind in one [of] its more sensitive epochs, the metaphor of ground and tremor completely lost their apparent innocence; they were no longer merely figures of speech" (263). Hamacher claims that the foundational certainty of Descartes' philosophy began to shake following the Lisbon earthquake.

The earthquake had a major impact on Portuguese politics. The prime minister was the favorite of the king, but the aristocracy despised him as an upstart son of a country squire (although Prime Minister Sebastião de Melo is known today as Marquis of Pombal, the title was only granted in 1770, fifteen years after the earthquake). The prime minister in turn disliked the old nobles, whom he considered corrupt and incapable of practical action. Before 1 November 1755 there was a constant struggle for power and royal favor, but the competent response of the Marquis of Pombal effectively severed the power of the old aristocratic factions. However, silent opposition and resentment of King Joseph I began to rise, which would culminate with the attempted assassination of the king, and the subsequent elimination of the powerful Duke of Aveiro and the Távora family.

Development of seismology

The prime minister's response was not limited to the practicalities of reconstruction. He ordered a query sent to all parishes of the country regarding the earthquake and its effects. Questions included:

- At what time did the earthquake begin and how long did the earthquake last?

- Did you perceive the shock to be greater from one direction than another? Example, from north to south? Did buildings seem to fall more to one side than the other?

- How many people died and were any of them distinguished?

- Did the sea rise or fall first, and how many hands did it rise above the normal?

- If fire broke out, how long did it last and what damage did it cause?[16]

The answers to these and other questions are still archived in the Torre do Tombo, the national historical archive. Studying and cross-referencing the priests' accounts, modern scientists were able to reconstruct the event from a scientific perspective. Without the query designed by the Marquis of Pombal, this would have been impossible. Because the marquis was the first to attempt an objective scientific description of the broad causes and consequences of an earthquake, he is regarded as a forerunner of modern seismological scientists.

The geological causes of this earthquake and the seismic activity in the region continue to be discussed and debated by contemporary scientists.

See also

- List of earthquakes

- Earthquake Baroque

- 1755 Cape Ann Earthquake

Notes

- ^ Between History and Periodicity: Printed and Hand-Written News in 18th-Century Portugal

- ^ Gutscher, M.-A.; Baptista M.A. & Miranda J.M. (2006). "The Gibraltar Arc seismogenic zone (part 2): Constraints on a shallow east dipping fault plane source for the 1755 Lisbon earthquake provided by tsunami modeling and seismic intensity". Tectonophysics 426: 153–166. Bibcode:2006Tectp.426..153G. doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2006.02.025. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ "Historic Earthquakes – Lisbon, Portugal." U.S. Geological Survey, October 26, 2009. {Estimate: 8.7}

- ^ Pereira (2006), page 5.

- ^ Viana-Baptista MA, Soares PM. Tsunami propagation along Tagus estuary (Lisbon, Portugal) preliminary results. Science of Tsunami Hazards 2006; 24(5):329 Online PDF. Accessed 2009-05-23. Archived 2009-05-27.

- ^ Memoirs of Casanova, Book 2, Ch. XXVI; Casanova himself noted feeling the shocks when he was imprisoned in "The Leads" in Venice and specifically states they were the same that destroyed Lisbon

- ^ Brockhaus' Konversations-Lexikon. 14th ed., Leipzig, Berlin and Vienna 1894; Vol. 6, p. 248

- ^ a b Lyell, Charles. Principles of Geology. 1830. Vol. 1, chapter 25, p. 439 Online electronic edition. Accessed 2009-05-19. Archived 2009-05-21.

- ^ Zitellini N. et al., The tectonic source of the 1755 Lisbon earthquake and tsunami. Anali di Geofisica 1999; 42(1): 49. Online PDF. Accessed 2009-05-23. Archived 2009-05-27.

- ^ Blanc P.-L. Earthquakes and tsunami in November 1755 in Morocco: a different reading of contemporaneous documentary sources. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2009; 9: 725–738. Online PDF. Accessed 2009-05-23. Archived 2009-05-27.

- ^ Pereira (2006), pages 8–9.

- ^ pages 33–9921.

- ^ Kendrick. The Lisbon Earthquake. p. 75. Kendrick writes that the remark is apocryphal and is attributed to other sources in anti-Pombal literature.

- ^ Gunn (2008), page 77.

- ^ Shrady, The Last Day pp. 152–155.

- ^ Shrady, The Last Day, pp.145–146

References

- Benjamin, Walter. "The Lisbon Earthquake." In Selected Writings vol. 2. Belknap, 1999. ISBN 0-674-94586-7. The often abstruse critic Benjamin gave a series of radio broadcasts for children in the early 1930s; this one, from 1931, discusses the Lisbon earthquake and summarizes some of its impact on European thought.

- Braun, Theodore E. D., and John B. Radner, eds. The Lisbon Earthquake of 1755: Representations and Reactions (SVEC 2005:02). Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 2005. ISBN 0-7294-0857-4. Recent scholarly essays on the earthquake and its representations in art, with a focus on Voltaire. (In English and French.)

- Brooks, Charles B. Disaster at Lisbon: The Great Earthquake of 1755. Long Beach: Shangton Longley Press, 1994. (No apparent ISBN.) A narrative history.

- Chase, J. "The Great Earthquake At Lisbon (1755)". Colliers Magazine, 1920.

- Dynes, Russell Rowe. "The dialogue between Voltaire and Rousseau on the Lisbon earthquake: The emergence of a social science view." University of Delaware, Disaster Research Center, 1999.

- Fonseca, J. D. 1755, O Terramoto de Lisboa, The Lisbon Earthquake. Argumentum, Lisbon, 2004.

- Gunn, A.M. "Encyclopedia of Disasters". Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008. ISBN 0-313-34002-1.

- Hamacher, Werner. "The Quaking of Presentation." In Premises: Essays on Philosophy and Literature from Kant to Celan, pp. 261–293. Stanford University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8047-3620-0.

- Kendrick, T.D. The Lisbon Earthquake. Philadelphia and New York: J. B. Lippincott, 1957.

- Neiman, Susan. Evil in Modern Thought: An Alternative History of Modern Philosophy. Princeton University Press, 2002. This book centers on philosophical reaction to the earthquake, arguing that the earthquake was responsible for modern conceptions of evil.

- Paice, Edward. Wrath of God: The Great Lisbon Earthquake of 1755. London: Quercus, 2008. ISBN 978-1-84724-623-3

- Pereira, A.S. "The Opportunity of a Disaster: The Economic Impact of the 1755 Lisbon Earthquake". Discussion Paper 06/03, Centre for Historical Economics and Related Research at York, York University, 2006.

- Quenet, Grégory Les tremblements de terre en France aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles. La naissance d'un risque. Seyssel: Champ Vallon, 2005.

- Ray, Gene. "Reading the Lisbon Earthquake: Adorno, Lyotard, and the Contemporary Sublime." Yale Journal of Criticism 17.1 (2004): pp. 1–18.

- Seco e Pinto, P.S. (Editor). Earthquake Geotechnical Engineering: Proceedings of the Second International Conference, Lisbon, Portugal, 21–25 June, 1999. ISBN 90-5809-116-3

- Shrady, Nicholas, The Last Day: Wrath, Ruin & Reason in The Great Lisbon Earthquake of 1755, Penguin, 2008, ISBN 978-0-14-311460-4

- Weinrich, Harald. "Literaturgeschichte eines Weltereignisses: Das Erdbeben von Lissabon." In Literatur für Leser, pp. 64–76. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 1971. ISBN 3-17-087225-7. In German. Cited by Hamacher as a broad survey of philosophical and literary reactions to the Lisbon earthquake.

External links

- The Lisbon earthquake of 1755: the catastrophe and its European repercussions. Archived

- The 1755 Lisbon Earthquake, available seismological studies from the European Archive of Historical EArthquake Data

- The 1755 Lisbon Earthquake

- Images and historical depictions of the 1755 Lisbon earthquake

- More images of the 1755 Lisbon earthquake and tsunami

- Contemporary eyewitness account of Rev. Charles Davy

- Description of the Pan-European consequences of the earthquake and tsunami, by Oliver Wendell Holmes.

- No Source for Hanging-Priests Calumny